Stop

- Katakana English: ストップ

- sounds like: suTOH-PPu

- English origin word: stop!

- Actual Japanese word: やめて (imperative)

This is a political poster from the Japanese Communist party opposing the increase of the national consumption tax (sales tax) from 5% to 10%. Rather than using any one of a number of Japanese words that would effectively convey their opposition, they went with an English word spoken with a Japanese accent.

「ストップ」is also widely used instead of 「止まれ」 when telling the driver of a car to stop or「立ち止まれ」as a direction from parents to their children to keep them from running into the street.

Evening Good!Set

- Katakana English: イブニン

- sounds like: EE-BOO-NEEN

- English origin word: evening

- Actual Japanese word: 夕方 (yoo-gah-tah), 夜 (yoh-roo)

First of all, in the katakana dictionary, ‘evening’ becomes「イブニング」, not 「イブニン」, so the good people at Pronto Café can’t even do bad Japanese-English right. The top line reads: “limited menu until 8pm”. But I’m not really sure what an “Evening Good!” set would be. Maybe they’re getting English lessons from the Incredible Hulk. Or maybe they meant “good evening” (you know, instead of ‘good morning’ or ‘good afternoon’). Or if they really want to be cool and use English, maybe they could ask a native speaker and find out that we have a magical term called “happy hour” that would get the point of this promotion across.

I’m also puzzled why they transliterated ‘evening’ into katakana but then left the other two words in English. Why not イブニング・グッド・セット? Or better yet, use Japanese: 良い夕方セット!

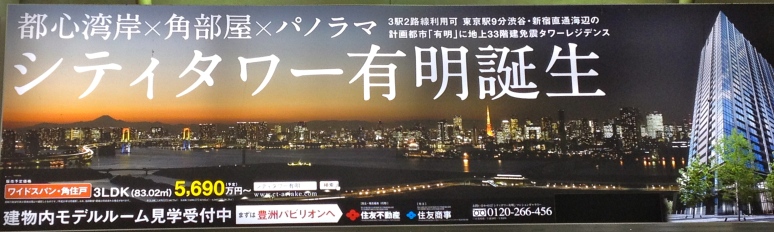

Shitty Tower

- Katakana English: シティタワー

- sounds like: SHITI TAH-WAAH

- English origin word: city tower

- Actual Japanese word: 都市タワー(toshi tah-waah), 都市塔(toshi-toh)

Here the katakana words are a proper noun, ‘City Tower,’ the name of a new high rise condominium building. I can easily forgive the use of words from a foreign language in this case since English speaking countries also often borrow names from other languages, especially French, to make shopping centers, residential areas, and the like sound classy. But in this case the use of ‘city’ is a poor choice. Yes, the stereotype is true: Japanese, like most Asian languages, lacks a sound for sih. The closest they have is shi. So when they talk about this place, what comes out isn’t ‘City Tower,’ but rather ‘shitty tower.” Doesn’t sound like such a classy place to live after all.

Sandwich

- Katakana English: サンド

- sounds like: SAHN-DOH

- English origin word: sandwich

- Actual Japanese word: none

This is one of my all-time favorite examples of misuse of English in the Japanese language. Not only does the Japanese language often import English words, it’s also prone to shortening things when possible. That’s whyリモートコントロール (remote control) got shortened to リモコン and エアコンディショナー (air conditioner) became エアコン; English words are just longer than Japanese words. Usually I’m puzzled by the adoption of the English word when there’s a perfectly good Japanese word that they’ve apparently decided isn’t cool enough anymore. But in this case, ‘sandwich’ is a Western concept for which there is no Japanese term. Fair enough. But when you then go and shorten サンドイッチ (SAHN-DOH-EETCH) to just サンド and then go and write it English, you might want to check the dictionary and make sure it doesn’t happen to mean something else! 英語の「sand」って言う言葉は「砂」と定義します。I would also be remiss if I didn’t note that in the picture above, this isn’t even a sandwich, but rather a stack of pancakes!

Festival

- Katakana English: フェスタ

- sounds like: FES-tah

- English origin word: festival

- Actual Japanese word: 祭 (まつり / matsuri)

One of the strange things about the Japanese language is its seeming inability to evolve by expanding the meaning of words to encompass new or changing ideas. And festa is a good example of that. While Japanese has a word for festival, matsuri, it is only used for traditional Japanese festivals. Anything with a more modern flair, such as the flower festival above or the design festival below, are called festa. There really shouldn’t be anything wrong with「花祭り」(hana-matusri), but the event planners scrapped the Japanese words for both flower and festival. One of the problems with this shortened version of the English word ‘festival’ is that it often appears in posters written in English, so when Japanese speak in English they assume they’re using an actual English word which, of course, it isn’t.

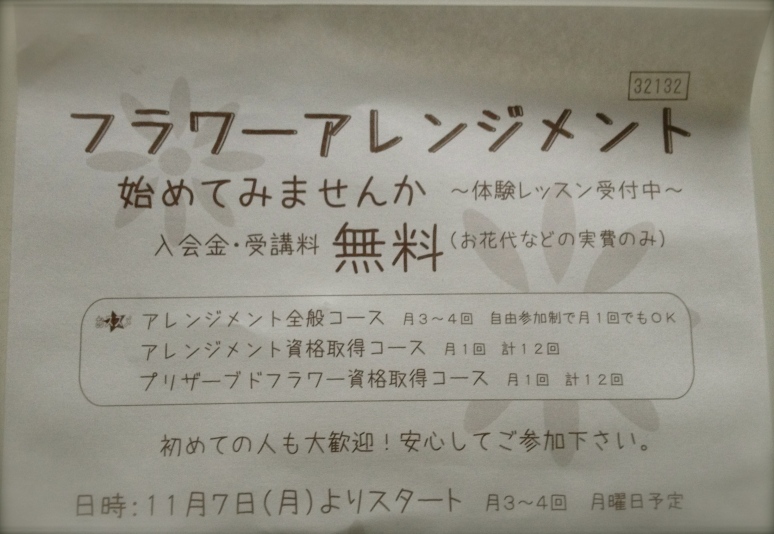

Flower Arrangement

- Katakana English: フラワーアレンジメント

- sounds like: FuRAH-WAH AhRANGE-MENTO

- English origin word: flower arrangement (flower arranging)

- Actual Japanese word: 生け花 (いけばな/ikebana)

This one puzzles me more than any other example, because not only is there already a Japanese word for this traditional Japanese art (and let me reiterate that point: it’s a TRADITIONAL JAPANESE ART!), it’s one of those few Japanese words that English speakers already know: ikebana!!

Reform

- Katakana English: リフォーム

- pronunciation: REE-FOH-Mu

- English origin word: reform

- Actual Japanese word: 改造 (かいぞう / kaizou)

Explanation:

Aside from the unintentionally hilarious use of “homey,” (Whaddup, corporation!) this sign for a remodeling company is an example of 和製英語 (wasei-eigo), or Japanese-English, where a word taken from English is used to mean something totally different. Again, there’s a perfectly good Japanese word that means exactly the same thing (改造) – in this case it’s on the sign with the wasei-eigo term.

What’s Wrong:

Here, ‘reform’ is used to mean ‘remodel,’ whereas native English speakers use ‘reform’ to talk about changing and improving a system or organization, as in ‘educational reform’ or ‘political reform.’ As with all wasei-eigo words, the real damage comes when Japanese students of English say ‘reform’ when they mean ‘remodel,’ causing confusion in the conversation. They naturally assume that since the word came from English, they know what it means. But I think it’s better to stick to Japanese words when speaking Japanese and English words when speaking English.

Clean Politics

- Katakana English: クリーン

- sounds like: KuREEN

- English origin word: clean

- Actual Japanese word: きれいな, 汚れのない

Even though there are words for “clean” and “dirty” in Japanese, when it comes to conveying a sense of “clean politics” as the election poster above does, they decided it was better to just use the English word instead. This one baffles me because I simply can’t imagine an American politician using a foreign word as part of a campaign slogan; it would be career suicide.

Unbelievable!

- Katakana English: アンビリーバボー

- sounds like: AHN-BE-REE-BAH-BOH

- English origin word: unbelievable

- Actual Japanese word: 凄い (すごい / sugoi)

Katakana is generally used for imported vocabulary, for things or ideas that are foreign to Japan. And that’s why this one really shocked me. There’s already a word that expresses this sentiment, and it’s not exactly obscure. You only have to listen in on any conversation for a minute and someone is bound to exclaim “すごい!” or its hipper variant “すげぇぇ!” アンビリーバボー is also long and not that easy to say. It would be like English speakers replacing “cool” with some hard-to-pronounce Chinese word!

Nohongo

I met my first Japanese friends in college more than ten years ago and started studying Japanese because of them. I’ve lived in Japan for seven of the last nine years and while my Japanese is good, it should be better.

I passed the Japanese Language Proficiency Test, level 2, in 2006. I’ve taken the level 1 exam twice and failed both times. When I show the level 1 grammar and vocab to my Japanese friends and co-workers, the reaction is the same: they’re surprised because they don’t even know half of it. And If they don’t know it, why should I?

While I think it would be nice to say I’ve passed level 1, I know it doesn’t matter. I can more than get by in daily life. I’ve just lost my motivation to continue studying Japanese. Partly, it’s because my job is teaching English, so I don’t get many chances to speak Japanese. But the main reason is the change in the Japanese language itself. It has become increasingly trendy to use “katakana English” – words borrowed from English and pronounced with the Japanese syllabary – instead of native Japanese words. So, why should I endeavor to learn new vocabulary when I can communicate just as effectively using English words I already know, spoken in a Japanese accent?

This blog will serve as a platform for me to make the case that, once you reach an intermediate level of Japanese, there’s really no point in struggling to master the language. I will show how the Japanese are replacing their language with mine, so there’s no need for me to make any further effort.

-

Recent Posts

Archives

Categories

Meta